Online US Privacy Laws State by State – Is Your Data Safe in 2025?

Categories: Data, Data Privacy, Law, Policy

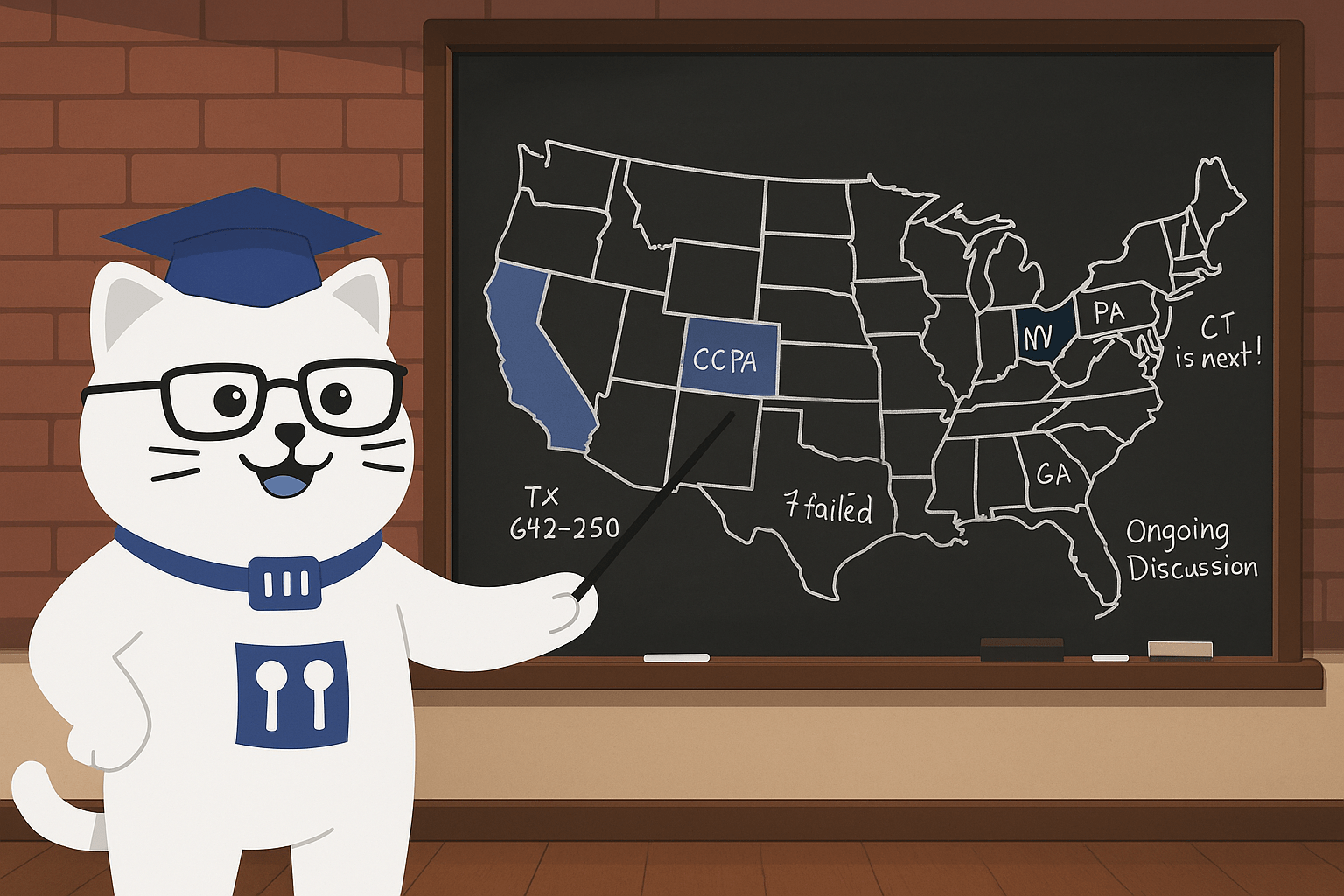

The year the patchwork became a quilt: how U.S. state online privacy laws have finally hit critical mass

2025 turned a patchwork of state privacy rules into a workable baseline across much of the United States.

Universal opt out is moving from idea to requirement, browsers can send a single signal that sites must honor in many states.

Health data outside HIPAA, sensitive location and app telemetry, is now restricted under new state laws.

More nonprofits and smaller companies are in scope, data minimization and sensitive data opt in are becoming the norm.

Privacy Law Update for Specific States:

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Florida

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kentucky

- Maryland

- Minnesota

- Montana

- Nebraska

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- Oregon

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Virginia

Introduction – US Privacy Law Update (2025)

For years, American privacy law looked like a half-finished puzzle. California dominated one corner, a few early adopters sprinkled pieces around the edges, and the center stayed stubbornly blank. In 2025, the picture finally started to come into focus. A wave of state statutes took effect, older laws gained sharper teeth through rulemaking and enforcement, and new sector rules filled gaps federal law never reached. The country still does not have a single national privacy statute, yet a functional baseline has emerged, stitched together by states that increasingly agree on core consumer rights and corporate responsibilities. The details still vary. The spirit has changed. Consumers can now exercise real choices in more places, and companies can no longer treat privacy as a California-only project.

This shift arrived for three reasons. First, copycat momentum turned isolated experiments into a pattern. Virginia’s early controller and processor model gave lawmakers a template. Colorado and Connecticut pushed automated opt outs through universal preference signals. Texas and Nebraska broadened who counts as a covered business. Second, enforcement matured. Attorneys general created privacy units, issued guidance, and signaled that cure periods are not a hiding place. Third, lawmakers targeted data that had lived in the shadows of traditional health and financial rules. Location pings near clinics, wellness app telemetry, and granular adtech profiles now sit in the open. The result is not a perfect quilt. It is, however, a real one.

What follows is a tour of the most consequential state laws now in force or on the near horizon, the practical rights they create, and the obligations they impose.

California

California remains the bellwether. The state’s original consumer privacy law, strengthened by voter initiative, still sets the high-water mark for individual rights and company duties. Regulators have continued to refine the rules, with growing attention to risk assessments, automated decision-making, and the mechanics of honoring opt outs. California also operates the nation’s most muscular data broker regime. Registration is mandatory and a statewide mechanism for deletion requests is phasing in, which will reduce the scavenger hunt consumers face when they try to clean up their digital trails. A broad kids’ design code remains tied up in court, which means the state’s approach to children’s safety may arrive through narrower, targeted bills rather than one sweeping standard.

What to expect: Persistent leadership on deletion and sensitive data. More detail around automated systems and dark patterns. Continued friction around children’s online protections while litigation unfolds.

Colorado

Colorado was early on universal opt out and has treated it as a real, operable right rather than packaging for a cookie banner. If a browser or device sends a recognized signal, covered sites must treat it as a command to stop targeted advertising and the sale of personal data. The state’s guidance focuses on practical implementation and on the idea that privacy should be designed in, not bolted on through pop ups.

What to expect: Normalization of browser-level controls. More assessments for high-risk processing. Ongoing coordination with other states on what counts as a valid opt-out mechanism.

Connecticut

Connecticut arrived at a similar destination. Controllers covered by its law must honor opt-out preference signals for targeted advertising and data sales. The statute also brought health-adjacent data into scope through amendments that mirror broader national anxieties about wellness apps and location tracking.

What to expect: Continued alignment with Colorado on universal signals. Incremental expansion of sensitive-data safeguards.

Delaware

Delaware’s comprehensive law took effect Jan 1, 2025 with a familiar suite of rights. Residents can access, correct, delete, and port their data. Controllers must obtain opt-in consent for sensitive categories and must conduct assessments for high-risk processing. For a small state with outsized corporate presence, the law’s impact extends beyond its borders. Universal opt-out mechanisms are required from Jan 1, 2026.

What to expect: A steady program that looks and feels like the modern norm, backed by an attorney general that oversees many companies incorporated in the state.

Florida

Florida’s Digital Bill of Rights has a narrow aperture that focuses on very large businesses and certain platform operators. It set out duties around disclosures, data minimization, and children’s profiling. The scope means many companies escape coverage, at least for now.

What to expect: Potential broadening through follow-on legislation. Increased scrutiny for the narrow set of covered giants.

Indiana

Indiana enacted a Virginia-style framework with a future effective date in 2026. The structure will feel familiar to compliance teams. The runway is deliberate, which gives multistate companies time to harmonize programs.

What to expect: A conventional start when the law takes effect. Fewer surprises, more housekeeping.

Iowa

Iowa’s law went live with a lighter touch. Core rights are present. Universal opt-out signals are not mandated under the statute. The state chose more business-friendly thresholds and a compliance posture that favors predictability.

What to expect: Stable obligations with fewer automation requirements. Companies can typically satisfy Iowa by extending existing programs.

Kentucky

Kentucky passed a Virginia-style statute with an effective date in the near future. Universal opt-out recognition is not required. The state offers a cure period that does not sunset, which suggests an enforcement approach focused on correction rather than punishment.

What to expect: Familiar rules that align with Virginia and Indiana. An emphasis on notices, consent for sensitive data, and assessments for high-risk activities.

Maryland

Maryland stepped into the front rank with a strict data minimization rule and comparatively fewer carve outs. The state’s law narrows exemptions that many companies have come to rely on, which broadens resident protections and pushes organizations to justify every category of data they collect. Maryland also passed a kids-focused measure, reinforcing a trend toward age-aware design even where omnibus efforts face legal challenges.

What to expect: Deeper questions from regulators about necessity and proportionality. Less room for broad sectoral exemptions. Early test cases that define what counts as strictly necessary.

Minnesota

Minnesota’s comprehensive law includes the usual suite of rights along with distinctive provisions for profiling, documentation, and teens’ data. The statute limits the sale of personal data for people aged 13 to 16 and puts more weight on internal governance.

What to expect: More attention to what your models do, not just what your notices say. Stronger paper trails and decision logs.

Montana

Montana already requires recognition of universal opt-out signals. The practical effect is simple. Residents who set a valid browser preference should not have to fight pop ups to stop targeted ads or the sale of their data.

What to expect: Increasing consumer awareness of set-it-once controls. Quiet but real compliance work on the back end.

Nebraska

Nebraska’s law resembles Texas in a key way. The scope is broad and does not lean on revenue thresholds, which pulls more businesses into coverage. The state attorney general has exclusive enforcement authority.

What to expect: Greater compliance outreach to smaller and mid-sized companies. Clarifications on what it means to do business in the state for jurisdictional purposes.

New Hampshire

New Hampshire’s modern framework arrived with standard rights and a cure window. The version is pragmatic and readable, which should help both residents and businesses understand what is expected.

What to expect: Incremental updates that keep the law aligned with the national middle. Clearer guidance as enforcement ramps.

New Jersey

New Jersey stands out for two reasons. It applies to nonprofits. It defines sensitive data broadly, which forces organizations that once assumed exemptions to examine their practices more closely. Universities, foundations, and charities must now treat privacy programs as core operations.

What to expect: New governance structures inside nonprofit institutions. More formal data-mapping and consent practices where informal norms once prevailed.

Oregon

Oregon’s law took effect for most entities last year and extends to nonprofits this year. The state set a timetable for recognizing universal opt-out signals and for the end of a statutory cure period. The Pacific Northwest now functions like a region with consistent privacy expectations.

What to expect: A clean handoff from education to enforcement. Coordinated messaging with neighboring states about universal signals.

Tennessee

Tennessee introduced the first statutory safe harbor tied to the NIST Privacy Framework. The law does not eliminate duties, but it creates a path to demonstrate reasonableness and to reduce enforcement risk through structured governance.

What to expect: More companies adopting NIST artifacts such as profiles and implementation tiers. Auditors asking whether the safe harbor was pursued and why.

Texas

Texas built a broad statute that captures many businesses operating in the state. The law includes authorized agent provisions that allow people to direct opt outs through intermediaries. The attorney general signaled an appetite for enforcement by creating a dedicated privacy function.

What to expect: Letters and settlements that shape national practice. More companies treating Texas as a bellwether for scope and for practical compliance timelines.

Utah

Utah’s law predates the 2025 wave and takes a more restrained approach. The thresholds are higher, and certain duties are lighter than in Colorado or Connecticut. For companies that already built programs for stricter states, Utah tends to be incremental.

What to expect: Modest updates that preserve predictability. Limited movement on universal opt-out automation unless driven by national harmonization.

Virginia

Virginia remains the model that many states copied. The concepts of controller and processor, assessments for high-risk processing, and a notice and cure approach to enforcement all originated here in modern form. As newer states add features like universal opt out and stricter minimization, Virginia functions as a stable base that others layer upon.

What to expect: Continued relevance through harmonization. Companies will keep using Virginia as the backbone of policies and vendor contracts, then extend for stricter jurisdictions.

Health data privacy that goes beyond HIPAA

Two state laws reshaped the perimeter around health-adjacent data. Washington’s law regulates consumer health data far outside the boundaries of traditional medical privacy and bans geofencing around sensitive health facilities. Nevada adopted a similar approach that reaches wellness apps and data brokers who trade in inferences. Together these laws reframe what counts as health information online. The reach is not confined to hospitals or insurers. A period tracker, a meditation app, or a location dataset near a clinic now sits under more restrictive rules.

What to expect: More private lawsuits where authorized and more geofencing restrictions around sensitive places. New vendor due diligence for any product that touches health-adjacent data.

The universal opt-out decade

If the first chapter of American privacy was about creating rights, the next chapter is about automating them.

Universal opt-out mechanisms let people set a single preference once in the browser or device and have covered sites honor it. States are converging on this idea. Colorado already requires it. Connecticut and Montana followed. Oregon is on a timetable. Texas layered in authorized agents.

This shift turns privacy from a scavenger hunt of banners and toggles into a background signal that companies must respect. It also pushes design work into the product itself, since ignoring a valid signal is no longer a viable option. Full enforcement is expected from 2026.

Will Congress act

A federal privacy bill once again made noise in Washington, then stalled. Preemption remains the political stumbling block. States do not want to surrender hard-won protections, and industry wants a single standard that limits patchwork risk. The Federal Trade Commission’s broader rulemaking on commercial surveillance continues at a slow pace. The center of gravity remains in the states. If Congress eventually acts, it will have to be at least as strong as the strictest state laws or it will be accused of lowering the bar.

What this means for people

For the first time, the typical person in many states can press one button and tell sites to stop using their data for targeted advertising and sales. They can request access to the data companies hold, fix mistakes, and delete information that no longer needs to be kept. They can limit the use of sensitive categories such as precise location, biometric identifiers, and health information. They can do this without navigating a maze of pop ups, forms, and dead ends. The rights are not perfect and they are not universal, but they are real.

What this means for companies

The age of privacy theater is over. Regulators and courts are looking for proof of necessity, not just polished notices. Companies need data maps that go beyond inventory and reach into purpose, retention, and risk. They need to honor universal signals without breaking analytics or core functions. They need vendor contracts that reflect controller and processor roles with specificity. They need an intake and response process for data rights that scales. For smaller teams, the most practical strategy is to build to the strictest obligations in your footprint and then document where the law lets you step down.

Fast reference for 2025 milestones

January 2025 brought a cluster of laws online at once: Delaware, Iowa, Nebraska and New Hampshire all went live, and New Jersey followed later that month. Texas, on the same date, switched on its authorized-agent and universal-signal pieces, and Connecticut began treating universal opt-out signals as a real, enforceable control. By mid-year, Oregon’s coverage expanded to nonprofits and Tennessee’s NIST-tied safe harbor arrived; Minnesota joined with extra guardrails for teens. October pulled Maryland into the front rank with strict data minimization and fewer exemptions than most peers. A final group – including Delaware’s and Oregon’s universal-signal requirements, plus Virginia-style laws in Indiana and Kentucky – is queued for January 2026, giving national teams one clean horizon to finish harmonizing before the next wave lands.

For consumers, that means real choices they can set once and have honored across multiple jurisdictions. For companies, it means the days of privacy programs that start and stop at a single state line are over. The United States still lacks an omnibus federal law – but in practice, 2025 is the year the state-by-state quilt started to feel like a blanket.