Should the Government Regulate Social Media?

Categories: Data, Data Privacy, Data Safety, Government, Instagram, Policy, Social Media, TikTok

Social media platforms have gone from being casual hangouts to global powerhouses that shape the way people think, vote, shop, and communicate. Billions of users log in to share opinions, consume information, and interact with communities that transcend borders. In many ways, these platforms now serve as the digital public square.

But with this level of influence comes risk. Questions around data privacy, concerns about harmful content, and the sheer power of a few corporations over the flow of information have fueled debate over whether governments should step in and impose regulations.

The question is far from simple. Regulation could offer guardrails against abuse, but it also risks overreach, censorship, and stifling innovation. Below, we’ll explore both sides of the debate, look at examples of existing approaches, and consider possible middle ground.

Why People Support Government Regulation of Social Media

Protecting Children and Teenagers

Platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat are especially popular among younger users. Parents, educators, and psychologists have raised alarms about the link between heavy social media use and issues like anxiety, depression, body image concerns, and online bullying.

In 2023/24, U.S. lawmakers advanced kids’ safety bills (notably the Kids Online Safety Act, which passed the Senate in July 2024 but hasn’t been enacted). Separately, Utah enacted the first state law putting age-verification responsibility on app stores (Apple/Google) rather than individual apps, with parental consent requirements for minors.

Regulation, in this context, is seen as a way to set universal safeguards so that companies cannot profit at the expense of children’s well-being.

Data Privacy and Surveillance

Social media companies collect enormous amounts of data, from browsing habits and location to political preferences. Critics argue that users rarely understand how much is being gathered or how it is used, often for targeted advertising. Cases like the Cambridge Analytica scandal demonstrated how personal data can be misused in ways that impact elections.

Stronger regulations could enforce transparency, limit data collection, and give users greater control over their information.

Preventing Monopolistic Power

The social media landscape is dominated by a handful of companies including Meta, X, TikTok, and YouTube. Their control over information flow is unprecedented, raising concerns about monopolistic practices. Governments have historically regulated industries where concentrated power could harm consumers or competition, from telecoms to oil.

Advocates argue social media should be no different – Google have been wrestling to keep their own monopoly in tact for years, and continue to do so, to this day.

Why Critics Oppose Government Regulation

Threats to Free Speech

The strongest argument against regulation is the risk of censorship. If governments have the authority to decide what content is acceptable, it could be used to silence dissenting voices or unpopular opinions. In democratic societies, this concern is especially sharp. One administration’s narrative might be another’s political opposition.

Critics argue that while harmful content is a problem, the responsibility should remain with platforms and their users, not governments, to decide what speech is permissible.

Risk of Over-regulation and Innovation Stagnation

The internet has thrived on flexibility and innovation. Strict regulation could make it harder for startups to challenge established players, reducing competition and creativity. Large companies may be able to absorb the costs of compliance, but smaller innovators could be pushed out before they ever get a chance to grow.

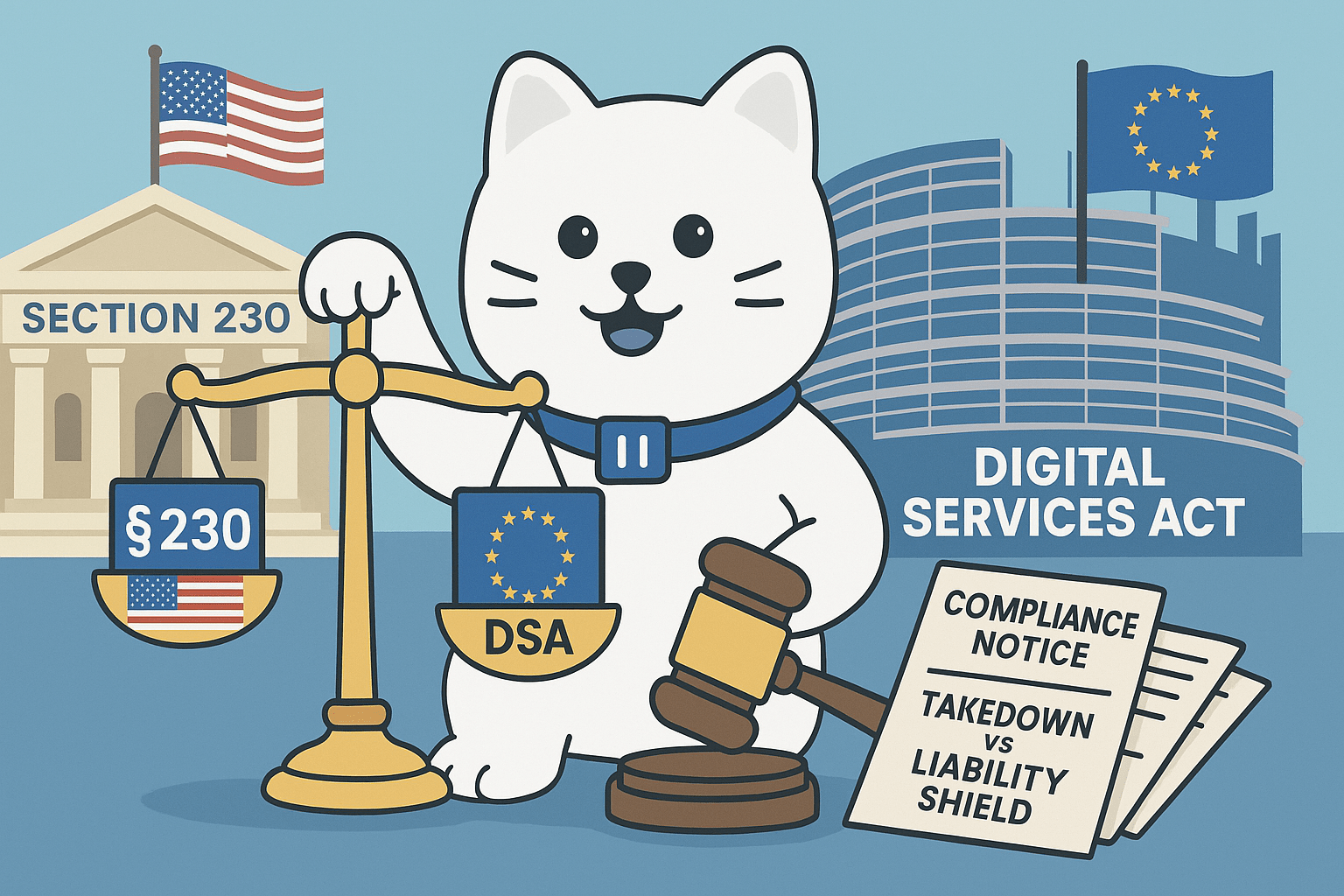

Global Complexity

Social media platforms operate across borders. Regulations in one country might clash with the laws of another. For instance, rules that apply in the European Union may not be enforceable in the United States or Asia. This raises questions about whether global platforms will have to fragment their services to comply with conflicting laws, which could ultimately harm users.

Private Sector Responsibility

Many argue that the private sector is best positioned to address the challenges. Platforms already have community guidelines, content moderation systems, and fact-checking partnerships. Governments stepping in could create duplication and unnecessary bureaucracy, while also politicizing content moderation decisions.

Real-World Examples of Regulation Efforts

Section 230 in the United States

One of the most important pieces of internet legislation is Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996. It shields platforms from liability for user-generated content while allowing them to moderate content in good faith.

Critics say it gives tech companies too much freedom without accountability. Some lawmakers want to reform or repeal it, arguing that companies should bear more responsibility for harmful content. Others warn that weakening Section 230 would devastate online communities and innovation.

Recently, a bipartisan proposal from Senator Durbin and Graham would sunset section 230 on Jan 1, 2027 unless Congress enacts a replacement – this is proposed legislation, not law.

The European Union’s Digital Services Act

The EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) applies broadly from 17 Feb 2024 (with ‘Very Large Online Platforms/Search Engines’ subject to obligations from Aug 25, 2023). The DSA doesn’t require publishing algorithms; instead, platforms must explain the “main parameters” of their recommender systems and provide user controls, publish ad transparency reports, and face fines up to 6% of global turnover for non-compliance.

This framework could become a global model if it proves effective without overly restricting free speech.

Other Global Efforts

- Australia’s 2021 News Media Bargaining Code required platforms to strike deals with publishers. In late 2024 the government proposed (and in 2025 moved forward with) a News Bargaining Incentive/tax to pressure platforms that don’t renew deals (e.g., Meta) to contribute or pay a levy.

- India’s IT Rules (2021) require intermediaries to remove or disable access to content within 36 hours of a court order or government notice, alongside other compliance duties.

- Brazil’s “Fake News” bill (PL 2630) passed the Senate in 2020 but remains pending in the Chamber of Deputies; efforts to advance it stalled in 2024/25 amid political pushback.

When Offensive Online Speech Becomes a Crime: The U.K. Example

The United Kingdom offers a real-world look at how governments can criminalize certain kinds of online speech. Unlike the United States, where the First Amendment sets a very high bar for restricting expression, the U.K. has a patchwork of criminal laws that police grossly offensive, threatening, or hateful content posted on social media. Police and prosecutors rely most often on Section 127 of the Communications Act 2003, the Malicious Communications Act 1988, and parts of the Public Order Act 1986. The newer Online Safety Act 2023 also updates offenses and adds platform-level duties to reduce illegal content.

Notable cases that led to jail or criminal penalties

- Liam Stacey, 2012

A university student received a 56-day jail sentence for racist tweets about footballer Fabrice Muamba after the player collapsed during a match. The case became an early flashpoint in the debate over whether offensive tweets should be criminal. - Matthew Woods, 2012

A 20-year-old was jailed for 12 weeks for posting highly offensive Facebook jokes about missing five-year-old April Jones. The case prompted the Director of Public Prosecutions to draft guidance on when to prosecute online offensiveness. - Mark Meechan (“Count Dankula”), 2018

A Scottish YouTuber was convicted for posting a video of a dog responding to Nazi phrases. He was fined rather than jailed, but the case is frequently cited in arguments that the U.K. criminalizes offensive jokes.

These are not isolated incidents. U.K. police have made thousands of arrests each year over online messages deemed grossly offensive, menacing, or causing distress.

Recent reporting indicates ~12,183 arrests in 2023 under the Communications Act 2003 s.127 and the Malicious Communications Act 1988 s.1 – arrests, not convictions – with convictions notably lower.

The laws most often used

- Communications Act 2003, Section 127

Criminalizes sending messages via a public electronic communications network that are grossly offensive, indecent, obscene, or menacing. A conviction can carry a fine or up to six months in prison. - Malicious Communications Act 1988

Targets messages intended to cause distress or anxiety, including threats and grossly offensive content sent to a person. - Public Order Act 1986 (stirring up hatred)

Criminalizes threatening, abusive, or insulting words or behavior intended, or likely, to stir up racial hatred. Social media posts can be investigated under these provisions, which sit alongside other hate-crime frameworks. - Online Safety Act 2023

Does not generally criminalize legal but harmful speech for users, but it modernizes communications offences and places new duties on platforms to remove illegal content quickly, disclose risk assessments, and mitigate systemic harms.

Supporters and critics

Supporters say these laws protect the public from targeted harassment, threats, and deliberate incitement. They point to the need for swift action when posts cause real-world harm or exploit tragedies. Critics argue that vague terms like grossly offensive give too much discretion to police and prosecutors, and that criminal penalties for bad jokes or crude opinions risk a chilling effect on everyday speech. Even U.K. officials and judges have periodically called for tighter, clearer thresholds for prosecution.

Why this matters to the regulation debate

For readers weighing government regulation of social platforms, the U.K. experience is a cautionary and instructive case. It shows that criminal law can and does reach into social feeds. It also shows how quickly enforcement can scale, and how hard it is to draw consistent lines between harmful conduct and protected expression. Any regulatory blueprint needs precise definitions, strong safeguards for lawful speech, and transparency about when and why enforcement happens, or it risks repeating the same controversies seen across the U.K. in the last decade.

Possible Middle Ground: Balancing Regulation and Freedom

The debate often gets framed as regulate or don’t regulate, but many experts argue the reality is more nuanced. Middle-ground approaches could include:

- Transparency requirements that force platforms to disclose algorithms, content moderation practices, and political ad targeting

- Data protection laws that limit what data can be collected and ensure users understand how their information is used

- Independent oversight boards to handle disputes over content moderation, reducing both government and corporate bias

- Youth protections such as standardized age verification, limits on addictive design features, and restrictions on harmful advertising directed at minors

- Accountability for bots and AI content through requirements to clearly label AI-generated posts

Such measures could address the most pressing issues without putting governments in charge of deciding what speech is permissible.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The influence of social media on daily life is only growing, and the debate over regulation will continue to intensify. Governments face pressure to act, especially in response to election security, youth mental health, and the spread of harmful online activity. At the same time, the risks of censorship, political abuse, and reduced innovation loom large.

Ultimately, the question is not whether regulation should exist, but what kind of regulation will preserve the benefits of open online platforms while protecting citizens from the worst harms. Striking this balance may prove to be one of the defining policy challenges of the 21st century.

Regardless of where social media legislation and regulations end up – one thing is certain, the space will become more heavily policed over time. Further, it is likely be house more bad actors over time, as cyber threats grow exponentially every year. The safest approach to social media is simple – minimization. Reduce the volume of content (especially anything sensitive) sitting online or in your DMs, tighten account privacy controls, and close accounts when they’re cleared. We wrote this comprehensive guide to get your social media footprint under control – you can start working through it for free, right now.